S R - 7 1 B l a c k b i r d

This is an incredible aircraft. If you have not heard of it, you will know what I mean by the

time you finish this article. It

was stationed at Edwards Air Force Base a few years ago, just a few miles from

Boron. I did not see it, but

Darlene did. I guess it was

something else to see flying in person.

Larry

Subject: S R - 7 1 B l a c k b i r d !

A really good read!

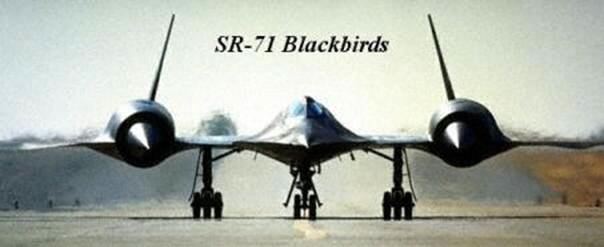

SR-71

Blackbird

In April 1986, following an attack on American soldiers in a Berlin disco,

President Reagan ordered the bombing of Muammar Qaddafi's terrorist camps in

Libya . My duty was to fly over Libya and take photos recording the damage

our F-111's had inflicted. Qaddafi had established a 'line of death,' a

territorial marking across the Gulf of Sidra , swearing to shoot down any

intruder that crossed the boundary. On the morning of April 15, I rocketed

past the line at 2,125 mph.

I was

piloting the SR-71 spy plane, the world's fastest jet, accompanied by Maj

Walter Watson, the aircraft's reconnaissance systems officer (RSO). We had

crossed into Libya and were approaching our final turn over the bleak desert

landscape when Walter informed me that he was receiving missile launch

signals. I quickly increased our speed, calculating the time it would take

for the weapons-most likely SA-2 and SA-4 surface-to-air missiles capable of

Mach 5 - to reach our altitude. I estimated that we could beat the

rocket-powered missiles to the turn and stayed our course, betting our lives

on the plane's performance.

After

several agonizingly long seconds, we made the turn and blasted toward the

Mediterranean.

'You might want to pull it back,' Walter suggested. It was then that I

noticed I still had the throttles full forward. The plane was flying a mile

every 1.6 seconds, well above our Mach 3.2 limit. It was the fastest we

would ever fly. I pulled the throttles to idle just south of Sicily,

but we still overran the refueling tanker awaiting us over Gibraltar.

Scores

of significant aircraft have been produced in the 100 years of flight,

following the achievements

of the Wright brothers, which we celebrate in December. Aircraft such as the

Boeing 707, the F-86 Sabre Jet, and the P-51 Mustang are among the important

machines that have flown our skies. But the SR-71, also known as the

Blackbird, stands alone as a significant contributor to Cold War victory and

as the fastest plane ever-and only 93 Air Force pilots ever steered the

'sled,' as we called our aircraft.

As

inconceivable as it may sound, I once discarded the plane. Literally. My

first encounter with the SR-71 came when I was 10 years old in the form of

molded black plastic in a Revell kit. Cementing together the long fuselage

parts proved tricky, and my finished

product looked less than menacing. Glue,oozing from the seams, discolored

the black plastic. It seemed ungainly alongside the fighter planes in my

collection, and I threw it away.

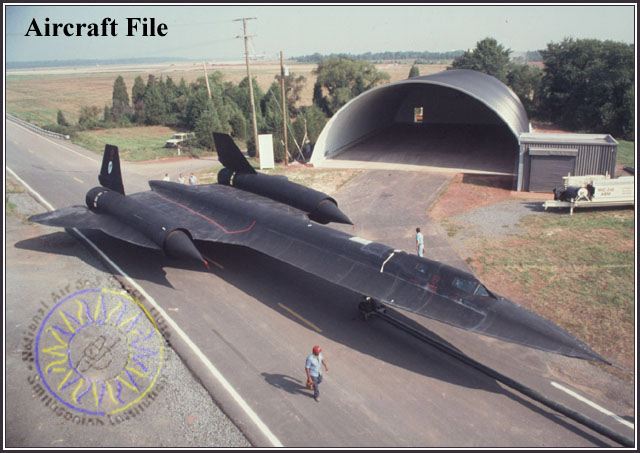

Twenty-nine years later, I stood awe-struck in a Beale Air Force Base

hangar, staring at the very real SR-71 before me. I had applied to fly the

world's fastest jet and was receiving my first walk-around of our nation's

most prestigious aircraft. In my previous 13 years as an

Air Force fighter pilot, I had never seen an aircraft with such presence. At

107 feet long, it appeared big, but far from ungainly.

Ironically,

the plane was dripping, much like the misshapen model had assembled in my

youth. Fuel was seeping through the joints, raining down on the hangar

floor. At Mach 3, the plane would expand several inches because of the

severe temperature, which could heat the leading edge of the wing to 1,100

degrees. To prevent cracking,

expansion joints had been built into the plane. Sealant resembling rubber

glue covered the seams, but when the plane was subsonic, fuel would leak

through the joints.

The SR-71 was the brainchild of Kelly Johnson, the famed Lockheed designer

who created the P-38, the F-104 Starfighter, and the U-2. After the Soviets

shot down Gary Powers' U-2 in 1960, Johnson began to develop an aircraft

that would fly three miles higher and

five

times faster than the spy plane-and still be capable of photographing your

license plate.

However, flying at 2,000 mph would create intense heat on the aircraft's

skin. Lockheed engineers used a titanium alloy to construct more than 90

percent of the

SR-71, creating special tools and manufacturing procedures to hand-build

each of the 40 planes. Special heat-resistant fuel, oil, and hydraulic

fluids that would function at 85,000 feet and higher also had to be

developed.

In 1962,

the first Blackbird successfully flew, and in 1966, the same year I

graduated from

high school, the Air Force began flying operational SR-71 missions. I came

to the program in 1983 with a sterling record and a recommendation from my

commander, completing

the weeklong interview and meeting Walter, my partner for the next four

years. He would ride four feet behind me, working all the cameras, radios,

and electronic jamming equipment. I joked that if we were ever captured, he

was the spy and I was just the driver. He told me to keep the pointy end

forward.

We trained for a year, flying out of Beale AFB in California , Kadena

Airbase in Okinawa, and RAF Mildenhall in England . On a typical training

mission, we would take off near Sacramento, refuel over Nevada, accelerate

into Montana, obtain high Mach over Colorado,

turn right over New Mexico, speed across the Los Angeles Basin, run up the

West Coast, turn right at Seattle, then return to Beale. Total flight time:

two hours and 40 minutes.

One day, high above Arizona , we were monitoring the radio traffic of all

the mortal airplanes below us. First, a Cessna pilot asked the air traffic

controllers to check his ground speed. 'Ninety knots,' ATC replied. A twin

Bonanza soon made the same request. 'One-twenty on the ground,' was the

reply.

To

our surprise, a navy F-18 came over the radio with a ground speed check. I

knew exactly what he was doing. Of course, he had

a ground speed indicator in his cockpit, but he wanted to let all the bug-smashers

in the valley know what real speed was 'Dusty 52, we show you at 620 on the

ground,' ATC responded.

The

situation was too ripe. I heard the click of Walter's mike button

in the rear seat. In his most innocent voice, Walter startled the controller

by asking for a ground speed check from 81,000 feet, clearly above

controlled airspace. In a cool, professional voice, the controller replied,

' Aspen 20, I show you at 1,982 knots on the

ground.' We did not hear another transmission on that frequency all the way

to the coast.

The

Blackbird always showed us something new, each aircraft possessing its own

unique personality. In time, we realized we were flying a national treasure.

When we taxied out of our revetments for takeoff, people took notice.

Traffic congregated near the airfield fences, because everyone wanted to see

and hear the mighty SR-71.

You

could not be a part of this program and not come to love

the airplane. Slowly, she revealed her secrets to us as we earned her trust.

One moonless night, while flying a routine training mission over the

Pacific, I wondered what the sky would look like from 84,000 feet if the

cockpit lighting were dark. While heading home on a straight course, I

slowly turned down all of the lighting, reducing the glare and revealing the

night sky. Within seconds, I turned the lights back up, fearful that the jet

would know and somehow punish me. But my desire to see the sky overruled my

caution, I dimmed the lighting again. To my amazement, I saw a bright light

outside my window. As my eyes adjusted to the view, I realized that the

brilliance was the broad expanse of the Milky Way, now a gleaming stripe

across the sky. Where dark spaces in the sky had usually existed, there were

now dense clusters of sparkling stars. Shooting stars flashed across the

canvas every few seconds. It was like a fireworks display with no sound. I

knew I had to get my eyes back on the instruments, and reluctantly I brought

my attention back inside.

To my surprise, with the cockpit lighting still off, I could see every

gauge, lit by starlight. In the plane's mirrors, I could see the eerie shine

of my gold spacesuit incandescently illuminated in a celestial glow. I stole

one last glance out the window.

Despite our speed, we seemed still before the heavens, humbled in the

radiance of a much greater power. For those few moments, I felt a part of

something far more significant than anything we were doing in the

plane.

The

sharp sound of Walt's voice on the radio brought me back to the tasks at

hand as I prepared for our descent.

San Diego Aerospace Museum

San Diego Aerospace Museum

The

SR-71 was an expensive aircraft to operate. The most significant cost was

tanker support, and in 1990, confronted with budget cutbacks, the Air Force

retired the SR-71?

The

SR-71 served six presidents, protecting America for a quarter of a

century.

Unbeknownst to most of the country, the plane flew over North Vietnam ,

Red China, North Korea , the Middle East, South Africa , Cuba , Nicaragua

, Iran , Libya , and the

Falkland Islands . On a weekly basis, the SR-71 kept watch over every

Soviet nuclear submarine and mobile missile site, and all of their troop

movements. It was a key factor

in winning the Cold War.

I am

proud to say I flew about 500 hours in this aircraft. I knew her well. She

gave way to no plane, proudly dragging her sonic boom through enemy

backyards with great impunity. She defeated every missile, outran every

MiG, and always brought us home. In the first

100 years of manned flight, no aircraft was more remarkable.

With the Libyan coast fast approaching now, Walt asks me for the third

time, if I think the jet will get to the speed and altitude we want in

time. I tell him yes. I know he is concerned. He is dealing with the data;

that's what engineers do, and I am glad he is. But I have my hands on the

stick and throttles and can feel the heart of a thoroughbred, running now

with the power and perfection she was designed to possess. I also talk to

her. Like the combat veteran she is, the jet senses the target area and

seems to prepare herself.

For the first time in two days, the inlet door closes flush and all

vibration is gone. We've become so used to the constant buzzing that the

jet sounds quiet now in comparison. The Mach correspondingly increases

slightly and the jet is flying in that confidently smooth and steady style

we have so often seen at these speeds. We reach our target altitude and

speed, with five miles to spare. Entering the target

area, in response to the jet's new-found vitality, Walt says, 'That's

amazing' and with my left hand pushing two throttles farther forward, I

think to myself that there is much they don't teach in engineering school.

Out my left window, Libya looks like one huge sandbox. A featureless brown

terrain stretches all the way to the horizon. There is no sign of any

activity. Then Walt tells me that he is getting lots of electronic

signals, and they are not the friendly kind.

The jet is performing perfectly now, flying better than she has in weeks.

She seems to know where she is. She likes the high Mach, as we penetrate

deeper into Libyan airspace. Leaving the footprint of our sonic boom

across Benghazi , I sit motionless, with stilled hands on throttles and

the pitch control, my eyes glued to the gauges.

Only the Mach indicator is moving, steadily increasing in hundredths, in a

rhythmic consistency similar to the long distance runner who has caught

his second wind and picked up the pace. The jet was made for this kind of

performance and she wasn't about to let an errant inlet door make her miss

the show. With the power of forty locomotives, we puncture the quiet

African sky and continue farther south across

a bleak landscape.

Walt continues to update me with numerous reactions he sees on the DEF

panel. He is receiving missile tracking signals. With each mile we

traverse, every two seconds, I become more uncomfortable driving deeper

into this barren and hostile land.

I am glad the DEF panel is not in the front seat. It would be a big

distraction now, seeing the lights flashing. In contrast, my cockpit is

'quiet' as the jet purrs and relishes her new-found strength, continuing

to slowly accelerate.

The spikes are full aft now, tucked twenty-six inches deep into the

nacelles. With all inlet doors tightly shut, at 3.24 Mach, the J-58s are

more like ramjets now, gulping 100,000 cubic feet of air per second. We

are a roaring express now, and as we roll through the enemy's backyard, I

hope our speed continues to defeat the missile radars below. We are

approaching a turn, and this is good. It will only make it more

difficult for any launched missile to solve the solution

for hitting our aircraft.

I push the speed up at Walt's request. The jet does not skip a beat,

nothing fluctuates, and the cameras have a rock steady platform.

Walt

received missile launch signals. Before he can say anything else, my left

hand instinctively moves the throttles yet farther forward. My eyes are

glued to temperature gauges now, as I know the jet will willingly go to

speeds that can harm her. The temps are relatively cool and from all the

warm temps we've encountered thus far, this

surprises me but then, it really doesn't surprise me. Mach 3.31 and Walt

is quiet for the moment.

I move my gloved finger across the small silver wheel on the autopilot

panel which controls the aircraft's pitch. With the deft feel known to

Swiss watchmakers, surgeons, and 'dinosaurs' (old- time pilots who not

only fly an airplane but 'feel it'), I rotate the pitch wheel somewhere

between one-sixteenth and one-eighth inch location, a position which

yields the 500-foot-per-minute climb I desire. The jet raises her nose

one-sixth of a degree and knows, I'll push her higher as she goes faster.

The Mach continues to rise, but during this segment of our route, I am in

no mood to pull throttles back.

Walt's voice pierces the quiet of my cockpit with the news of more missile

launch signals. The gravity of Walter's voice tells me that he believes

the signals to be a more valid threat than the others. Within seconds he

tells me to 'push it up' and I firmly press both throttles against their

stops.

For

the next few seconds, I will let the jet go as fast as she wants. A final

turn is coming up and we both know that if we can hit that turn at this

speed, we most likely will defeat any missiles. We are not there yet,

though, and I'm wondering if Walt will call for a defensive turn off our

course.

With no words spoken, I sense Walter is thinking in concert with me about

maintaining our programmed course. To keep from worrying, I glance

outside, wondering if I'll be able to visually pick up a missile aimed at

us. Odd are the thoughts that wander through one's mind in times like

these.

I

found myself recalling the words of former SR-71 pilots who were fired

upon while flying missions over North Vietnam They said the few errant

missile detonations they were able to observe from the cockpit looked like

implosions rather than explosions. This was due to the great speed at

which the jet was hurling away from the exploding missile.

I see nothing outside except the endless expanse of a steel blue sky and

the broad patch of tan earth far below. I have only had my eyes out of the

cockpit for seconds, but it seems like many minutes since I have last

checked the gauges inside. Returning my attention inward, I glance first

at the miles counter telling me how many more to go, until we can start

our turn. Then I note the Mach, and passing beyond 3.45, I realize that

Walter and I have attained new personal records.

The

Mach continues to increase. The ride is incredibly smooth.

There seems to be a confirmed trust now, between me and the jet; she will

not hesitate to deliver whatever speed we need, and I can count on no

problems with the inlets. Walt and I are ultimately depending on the jet

now - more so than normal - and she seems to know it. The cooler outside

temperatures have awakened the spirit born into her years ago, when men

dedicated to excellence

took the time and care to build her well. With spikes and doors as tight

as they can get, we are racing against the time it could take a missile to

reach our altitude.

It is a race this jet will not let us lose. The Mach eases to 3.5 as we

crest 80,000 feet. We are a bullet now - except faster. We hit the turn,

and I feel some relief as our nose swings away from a country we have seen

quite enough of. Screaming past Tripoli, our phenomenal speed continues to

rise, and the screaming Sled pummels

the enemy one more time, laying down a parting sonic boom. In seconds, we

can see nothing but the expansive blue of the Mediterranean .

I

realize that I still have my left hand full-forward and we're continuing

to rocket along in maximum afterburner.

The TDI now shows us Mach numbers, not only new to our experience but flat

out scary. Walt says the DEF panel is now quiet, and I know it is time to

reduce our incredible speed. I pull the throttles to the min 'burner range

and the jet still doesn't want to slow down. Normally the Mach would be

affected immediately, when making

such a large throttle movement. But for just a few moments old 960 just

sat out there at the high Mach, she seemed to love and like the proud Sled

she was, only began to slow when we were well out of danger.

I

loved that jet.

BACK TO EDITORIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS